Behind the story:

This story began with a conversation I overheard at a gas station. The cashier told a friend on the phone that she was working evenings to pay for her child’s daycare while she worked her day job.

When I began researching, I found that families in Delaware County pay more than Ball State University’s in-state tuition to send their children to daycare.

One of my passions is exploring how data can tell stories, but I knew that this issue was intensely human. When I began talking to parents, I learned how frustrating it was to find openings. When I talked to educators, I learned how important early learning is to them, but how burnt out they had become.

For the final story, I created page layouts, data visualizations, and illustrations.

Walking into the Mitchell Early Childhood and Family Center, visitors may notice a few things that are not typical of daycares. All the doors are propped open; walls and tables outside rooms are filled with art crafted from twigs, pinecones and rocks; children roam freely around the classroom; the playground is filled with logs and wooden spools.

Jennifer Young is an associate lecturer at Ball State University’s Department of Early Childhood, Youth and Family Studies and the campus liaison for the Mitchell Center. The center opened in 2019 at the former site of Mitchell Elementary School as a partnership between Ball State and the YMCA of Muncie.

The Mitchell Center’s unique approach to early learning, a style called the Reggio Emilia approach, is the source of many of those unique qualities.

“The Reggio Emilia style has an emphasis on respect for children,” Young said. “So children are really in charge of their own learning.”

Haley Butcher, a fourth-year family and child major at Ball State, first learned about the Mitchell Center through an infant and toddler development course that was held at the center’s lab school. After the class ended, she decided to apply for a part-time job there. Through her experiences there, Butcher learned that even though working with young children can be rewarding, it can also be difficult.

“I love it so much, but I didn’t realize how much of an emotional impact that it would have on me,” Butcher said. “Just knowing that with these kids, you’re teaching them everything from scratch.”

One of the challenges Young faces is keeping staff energized and connecting staff members. She said that they regularly plan pitch-in dinners, hold celebrations for big life events and give staff their birthdays off.

“It’s very draining, and when people get drained, they need the opportunity to be filled back up again,” Young said. “So this type of work is really work that needs multiple supports on a lot of different levels.”

In Indiana, child care providers are rated on the Paths to QUALITY scale, which assigns levels from one to four. Level one providers meet basic health and safety requirements, while level four providers are nationally accredited.

The Mitchell Center is rated level four under Indiana’s Paths to QUALITY program and accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. These advanced accreditations have stricter requirements, which can make finding qualified staff more difficult.

“There was a time period where we just really didn’t have people who are qualified to work in this field,” Young said.

Because the Mitchell Center is a lab school, Young said they rely on students like Butcher from Ball State, Ivy Tech and the Muncie Area Career Center to volunteer at the center as part of their course work. During the beginning of COVID-19, when classes went online, the Mitchell Center lost that help. Young also said the pandemic was difficult for those who worked through it.

“This is hard work to be in this field, and you need people that are physically-able, mentally-able, socially-able and emotionally-able to work with young children and their families,” she said. “The mental, emotional and social toll of COVID[-19] has really impacted us.”

Child care providers aren’t the only ones who have been affected by staff shortages. For parents, it can make an already daunting search even more difficult.

Isaiah Kimp, a second-year social studies teaching major at Ball State, called the Mitchell Center in March 2022 to add himself to their waitlist, just a month after he found out his girlfriend, Marisela Rodriguez, was pregnant.

Kimp’s son, Khepri, is now 7 months old and is still on the waitlist for the Mitchell Center. When the fall semester started in August 2022, Kimp had to scramble to find an opening at another provider so he and his girlfriend could start the semester.

“It became very frustrating when we both started class,” Kimp said. “What’s upsetting is that Muncie has daycares, but every day care has a waitlist, and my biggest challenge was trying to figure out how long each waitlist was.”

Chances and Services for Youth (CASY) is the child care resource and referral center that serves 24 counties in central Indiana, including Delaware County. Kristi Burkhart is the director of CASY’s child care resource and referral center, and Jennifer Lee is a community engagement specialist. Lee said staff shortages are one factor that is currently challenging child care providers in the area.

“Child care providers are needing staff. And because they are lacking staff, they are not able to fill the seats that they normally would — so the licensed capacity numbers are not being met right now,” she said.

Licensed capacity is an estimate of the amount of children each provider can care for while staying compliant with licensing standards. For example, there must be one caregiver for every four infants, and no more than eight infants per classroom. According to the Indiana Business Research Center, the number of child care workers still has not recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Unlike your gas station or your retail store where you might be able to work a little short-handed, child care is not one of those places,” Burkhart said.

When child care providers can’t meet capacity, Lee said parents are forced to search for other options. At CASY, Burkhart and Lee both help families deal with these situations on a daily basis. But it’s not just a job to them — it’s personal.

“We all have families, we’re all parents, we’ve all raised kids or have kids, and so we know the situation these families are in, and we know what it’s like looking for care,” Burkhart said.

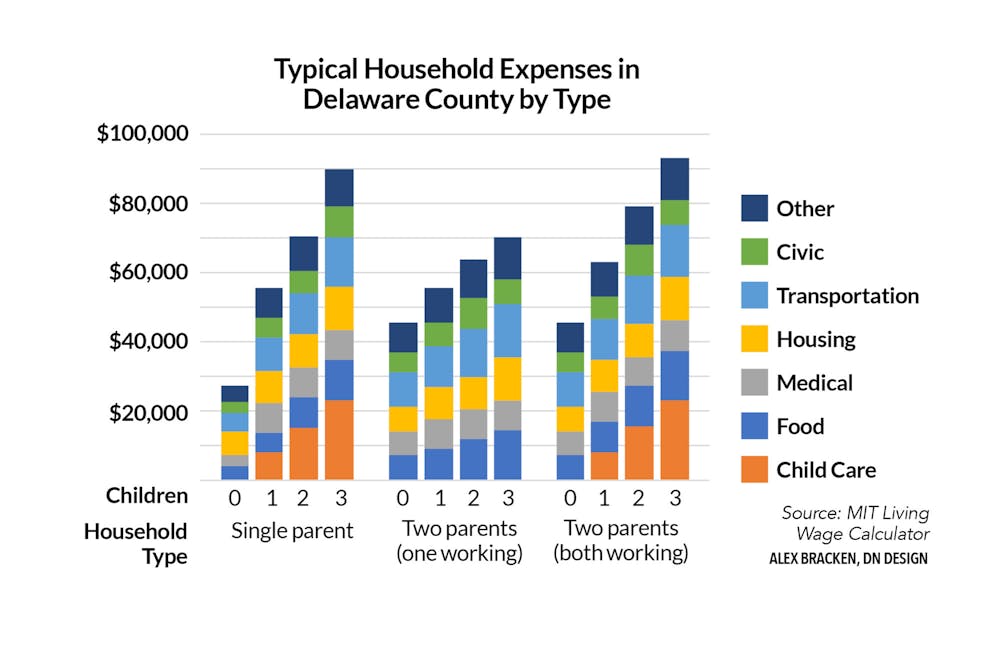

A large part of the work CASY and other agencies do is helping families find assistance with the cost of child care. According to Muncie BY5 Coalition, families in Delaware County pay an average of $10,731 each year to provide a child with high-quality childcare — more than Ball State’s annual in-state tuition, which is estimated to be $10,440 without room and board fees for the 2022-23 school year.

Prices vary widely based on the quality of care. According to Brighter Futures Indiana, the average cost of infant and toddler care from a level one provider is $8,727 annually and $12,245 for level three and four providers, which is considered “high-quality” child care.

For low-income families, assistance is available through Indiana’s Child Care Development Fund (CCDF). Eligibility varies, but generally families whose income is more than 27 percent below the federal poverty line are able to get help paying for child care while they are working, searching for a job or pursuing education. These vouchers are what help offset the cost of child care for Kimp and his son.

“Whatever the voucher doesn’t cover, me and his mom pay out of pocket for,” Kimp said. “And I never mind spending money on his child care because his child care is just as important as our needs.”

Burkhart said while finding care for children is a necessity, it can also be a difficult process for parents.

“In a lot of instances, families are looking for care for the first time, and they’re leaving their child with someone that they don’t know,” she said. “So our hearts go out to every one of these families we work with, and we just want to find the best solutions we can for them.”

For students like Kimp who have children, high-quality child care can give them the peace of mind to focus on their studies and their future.

“I’m going to do what I can to make sure … he’s taken care of by people who are trained and know what they’re doing, and as long as he’s safe and taken care of, I can go to class and focus on what I have to do to maintain what we have,” Kimp said.