It was 11 o’clock at night, and Mallorie Berger was looking through tax returns from her grandfather Alonzo Marshall’s business, trying to find any piece of information that could support her application for a historical marker. One by one, she typed names from the returns into Ancestry, hoping to find something that could help her search.

The second name on the list was Gerald Dixon, and her search returned an image of a selective service card, with a stamp reading “U.S. Prison Systems, Leavenworth Penitentiary” across it.

Berger said she gasped.

“I believe my grandfather Alonzo was a self-made millionaire, and I’m working to try to prove that,” Berger said. “But I’m thinking, ‘He’s making that kind of money, now he has a convicted felon working for him? Like, who is this person?’ But it doesn’t shock me, because my grandfather was such a kind person that he was willing to give everyone an opportunity.”

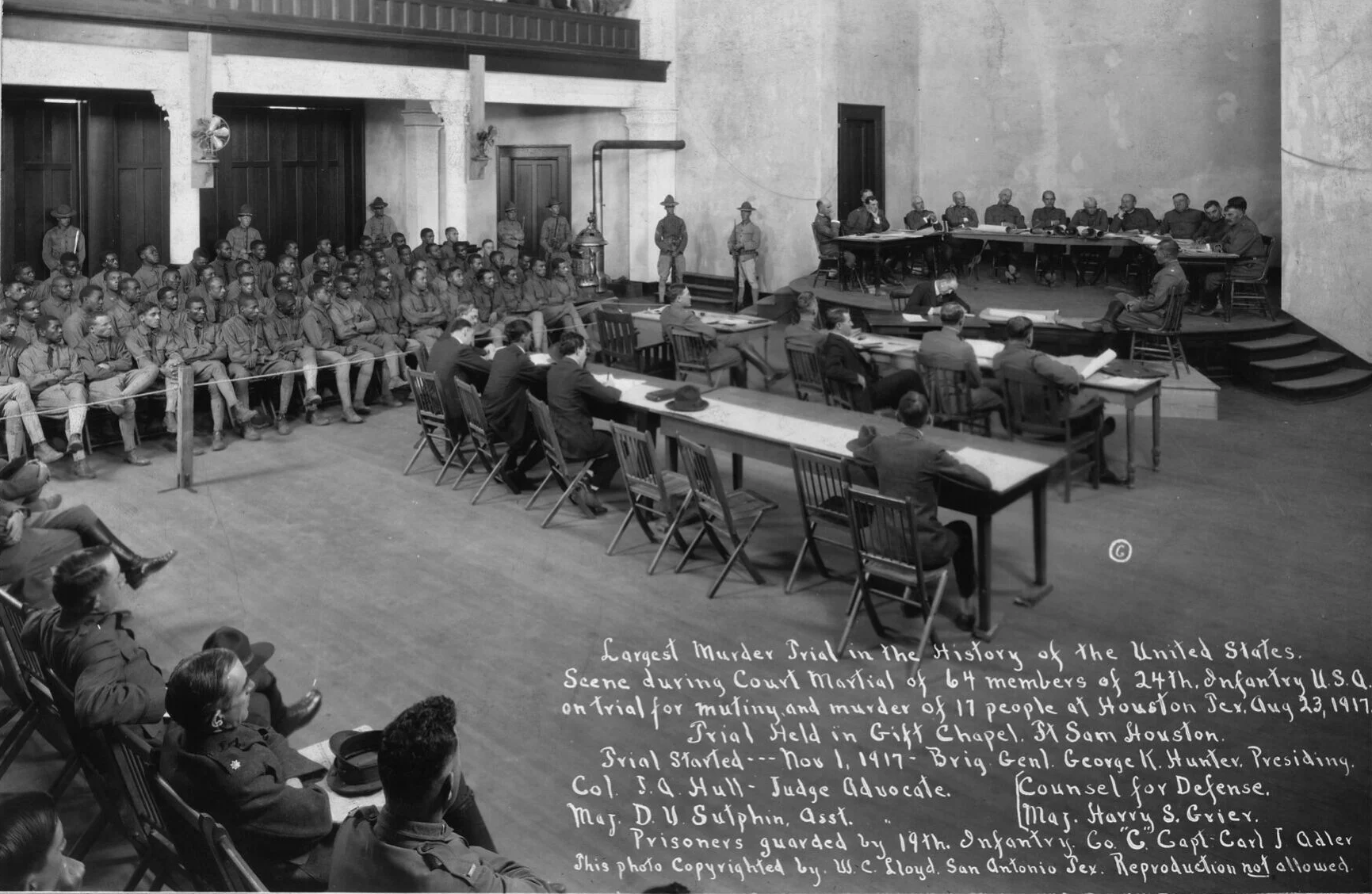

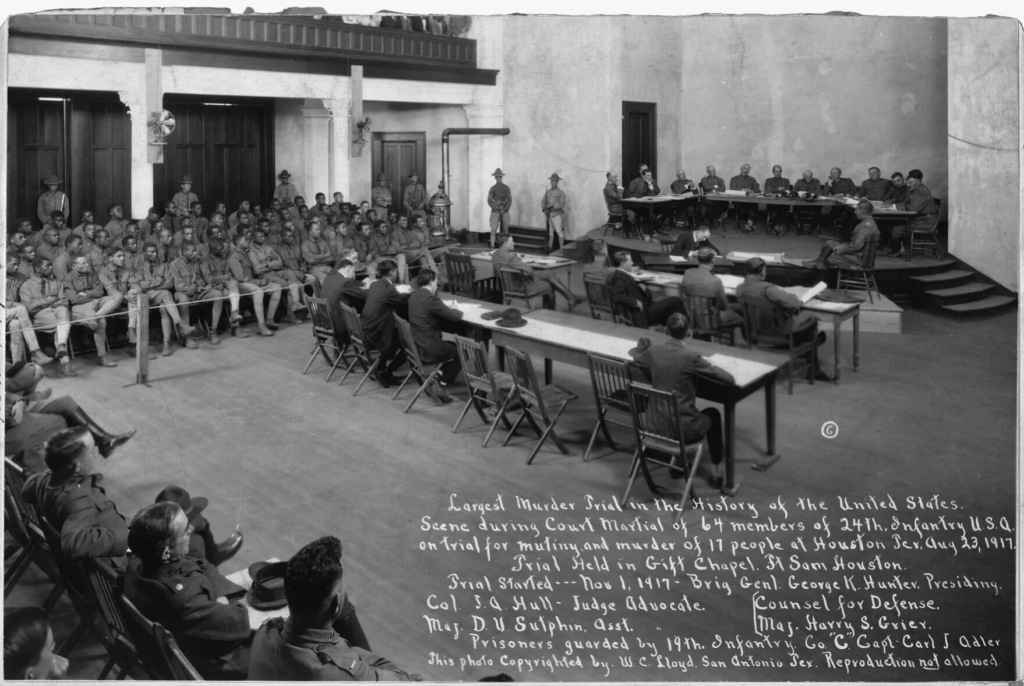

Berger followed her curiosity, eventually finding out that her father’s employee, Private Gerald Dixon, was one of 110 Buffalo soldiers convicted in the largest murder trial in American history, which occurred after a riot broke out between the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment and the racially hostile and all-white Houston Police Department in 1917.

The regiment of nearly 700 Black men was sent to Camp Logan in Houston, Tex., to guard the construction of a camp for white National Guard soldiers in 1917. Berger said the soldiers were harassed, discriminated against, and abused over the course of a couple months. Tensions escalated after one of the soldiers defended a Black woman who was being assaulted in town, and a riot eventually ensued after the Buffalo soldier was arrested by the Houston Police Department.

Dixon was sentenced to life in prison at Leavenworth Penitentiary for his alleged involvement, which was later shortened to 20 years by President J. Edgar Hoover. After serving seven years, Dixon was released on parole and returned to Marion. According to Eric Marshall, Berger’s brother, Dixon was their grandfather’s right-hand man.

19 of the 110 soldiers were executed, and 13 of those were hanged just two days after being convicted, with no chance to appeal their sentence. The soldiers’ families were not notified, and they were buried in unmarked graves in an undisclosed location. Six of the death sentences were later affirmed by President Woodrow Wilson, and executed.

However, all 110 of the convictions, including Dixon’s, were set aside by the U.S. Army in November 2023, after recognizing that the Buffalo soldiers “were wrongly treated because of their race and were not given fair trials,” according to the statement.

Berger and her brother, Eric Marshall, have been researching the life of Private Gerald Dixon for the past few months, and planning a weekend of events they hope will educate people about Dixon’s life, and bring him recognition for his service.

“There have been a lot of stories about this incident and the 24th Infantry Regiment that you can find if you do internet research,” Berger said. “But what you’re not finding are the stories of the individual folks. And for me, this is what is so important for me: to make sure that Gerald, who was a member of the 24th Infantry Regiment, but Private Gerald Dixon, is celebrated.”

The weekend will begin Saturday, Oct. 26, with a special event titled, “Buffalo Soldiers of the 24th: Camp Logan Riots and Marion’s Own Private Gerald Dixon,” which will be followed Monday with a graveside committal service, where Dixon and his wife, Francis, will be reinterred at the Marion National Cemetery with full military honors.

Berger said the support from the community has been overwhelming. Owen-Wellert-Duncan Funeral Home was quick to volunteer their funerary services, the Community Foundation of Grant County was able to contribute nearly $5,000 for the cost of the services through one of their funds, and Marion Mayor Ronald Morrell Jr. offered his team’s assistance with the event.

”It was just like, every time we started telling the story, people in Marion were like, ‘What do we need to do to help?’ … So it’s really started to grow legs, and I’m just so pleased that the community in Marion is really embracing the story,” Berger said.

The Saturday event will be held at Marion High School’s Walton Performing Arts Center at 1 p.m., and will feature a screening of a documentary that explores the history of the Buffalo Soldiers and the Camp Logan riot, and guest speakers.

The committal service will be preceded by a final salute and memorial caravan led by Marion Police and Fire Departments, and the National Association of Buffalo Soldiers and Troopers Motorcycle Club. The committal service will be held Monday at 2 p.m. at Marion National Cemetery, and is open to the public. Attendees should arrive at least 30 minutes before the service.

Berger said the community’s interest is a testament to Dixon’s story – the story of a man who experienced harsh discrimination and injustice while serving his country.

“For me, it’s just so heartwarming to see and to feel the love that is really being shown by my hometown. Everybody’s coming together, and excited, and wanting to see this man honored in death, since we couldn’t see him honored in life,” Berger said.

Dixon’s story is just the beginning for Berger, who plans to continue researching the history of Marion’s Black residents. She plans to replicate this weekend’s events for another Buffalo soldier in the 24th Infantry Regiment, who is buried in Bloomington. As she continues shedding light on history’s dark past for Black Americans, she said she has a simple motto.

“You know, I guess if I had to have my own little slogan, I would say: honoring history, rectifying recognition. And that’s what I’m doing with Gerald.”